The John H. Meier, Jr.

Governor General’s Literary Award Collection

Anne Dodertman, Acting Director of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

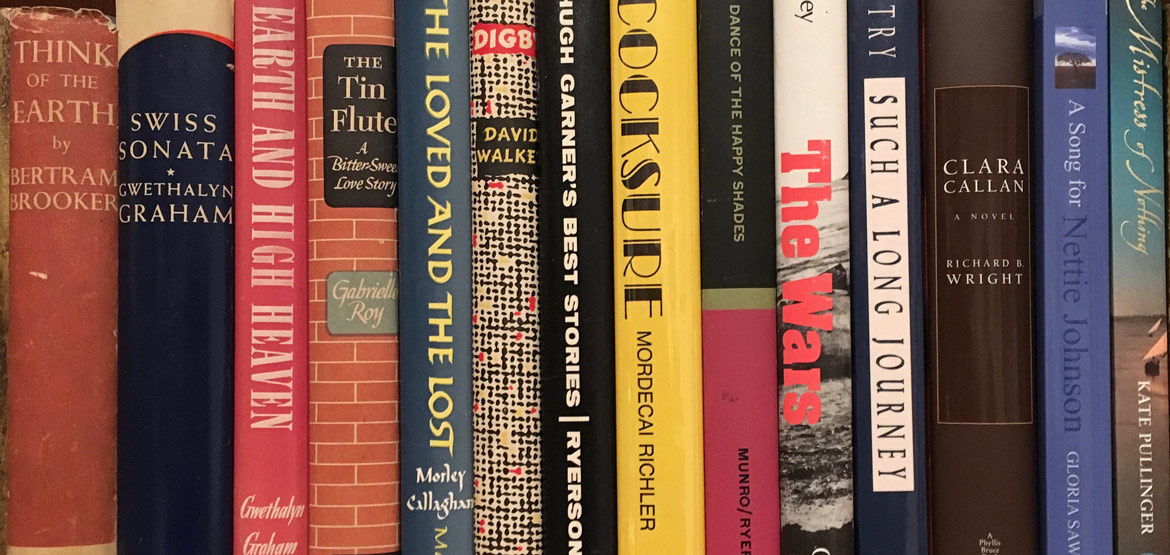

THIS WEBSITE PRESENTS examples of first editions of all the titles that have won Canada’s prestigious Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction (ggs) from its inception to the present. If we look at the list as a whole, it soon becomes apparent that it represents most of the great Canadian authors of the twentieth century. When the Award was first given, very few books were being printed in Canada; many of the early winners were published in the United Kingdom and the United States. The first editions chosen for this exhibit are the editions that were originally distributed in Canada. In some cases, especially the early titles, the British or American edition was the only edition distributed in Canada. (I have added a few American and British editions for a design comparison.) This collection thus gives a fascinating perspective on the history of publishing and printing in Canada in the twentieth century. I started this collection in late 1999 when, after almost 40 years of book collecting, chasing after the same literary high spots everyone else was pursuing, I began to think about uncharted areas of collecting that had been ignored or overlooked over the years. There are numerous literary awards in Canada: city, provincial, and national. During my research I came across the Governor General’s Literary Awards. The Awards, founded in 1937, were initially administered by the Canadian Author’s Association. I contacted the Canada Council for the Arts, a federal government organization that has been administering the Awards since 1959, to request a hardcopy of the cumulative list of winners. Upon reviewing it, I was surprised at how many winning titles I had read and enjoyed. However, many of the early titles had had decades to fall into obscurity, since they had not been reprinted.

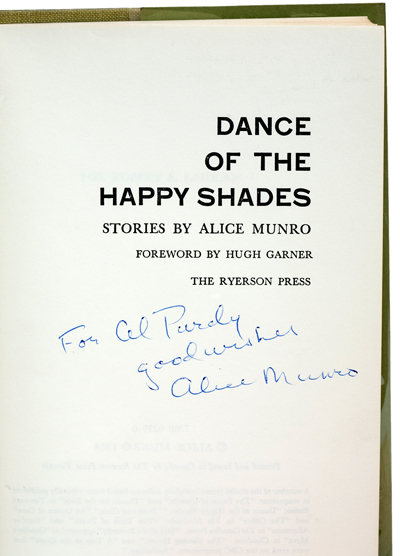

On another occasion, I heard from a local bookseller that the remaining books in poet Al Purdy’s collection had been bought by a rare book dealer in Victoria, BC. I immediately called the dealer and made arrangements to visit him the next day. I made the journey via BC Ferries early the next morning. This visit resulted in my purchase of half a dozen gg-winning titles inscribed to Purdy, who won two ggs himself for Cariboo Horses (1965) and The Collected Poems of Al Purdy (1986). In addition to his wonderful poetry, Purdy was a serious book collector who frequently asked fellow Canadian writers to inscribe his copies. One of the titles I bought that day, inscribed to the poet, was Alice Munro’s first book of short stories, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), in the first-issue dust jacket without the Award seal. There were only 2,675 copies printed of this, the first Ryerson Press edition. Another was the Lester & Orpen Dennys edition of Josef Škvorecký’s The Engineer of Human Souls (1984), also inscribed to Purdy.

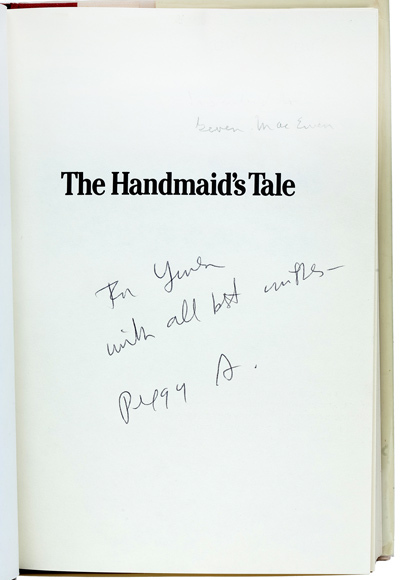

Association copies inscribed by one gg-winning author for another adds depth to the collection. Two great inscriptions in copies included in the exhibit are Dave Godfrey’s The New Ancestors (1970) inscribed on the half-title: ‘For Mrs. Jean Headon | Who made the library | which made me a writer. | Dave Godfrey | December, 1970,’ and a copy of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) inscribed to Gwendolyn MacEwen (two time gg winner for poetry) on the half- title: ‘For Gwen | with all best wishes- | Peggy A.’

I had been told at the beginning, by several booksellers and collectors, that I would not be able to locate many of the early Canadian editions since they were printed in such small numbers. I’ve always enjoyed a challenge, so this only further motivated me to complete the collection. I was also helped by changes in how books were sold. In the past it was a challenge to build a large collection of important books. The most common method of collecting, until recently, was to befriend booksellers who specialized in one’s area of interest. Additional ways to locate and buy rare and uncommon books included sending ‘want lists’ to various dealers, visiting used bookstores, attending book fairs, and requesting catalogues from dealers. Over the past fifteen years the Internet has dramatically changed the way the general public and collectors buy books. The Internet turned out to be the perfect tool for buying and selling books, which means dealers have almost entirely given up issuing catalogues. Numerous book-related websites sprung up in the early 1990s. I have also bought some great books on eBay. For example, I purchased my second copy of Bertram Brooker’s Think of the Earth on eBay. Since I might be the only serious collector of the Governor General’s Literary Award winners, I have had very little competition. I expect this to change.

In a matter of just a few years it seemed anyone could become a virtual bookseller. I believe there was a period of about four or five years when many incredible books were offered for sale. There was such an abundance of good books online that it appeared many were more common than was the case. It was too much of a good thing. Many collectors passed up opportunities to buy rare books, thinking that they could come back anytime to buy what they were looking for. Unfortunately, for some, those books are no longer easy to find. There are advantages and disadvantages to having so many books online. One of the disadvantages is that if you purchase a book from someone you have not dealt with in the past, you may be very surprised by what you receive. Many would-be booksellers do not know how to grade a book’s condition or even establish that it is a first edition, first printing. But then again, dealing with a novice bookseller you may just hit the jackpot! One of the advantages is that I have been able to purchase books from many places I would not have been easily able to contact by any other method. Thus I have purchased gg-winning titles from every province in Canada, a dozen US states, Switzerland, Britain, France, Australia, and New Zealand. The objective from the start was simple: obtain the best copies available. This collection of fiction titles consists of over 500 volumes of first editions in fine condition. It also includes various issues of the American, British, Canadian, and Australian first trade editions, galleys, uncorrected proofs, trial dust jackets, advance review copies, association copies, author copies, letters, and ephemera. It was important to locate copies in their original dust jackets for several reasons. The first is that this was how the publisher originally meant the book to be presented to the public. The second is that in some cases the dust jacket will establish whether the copy is a first printing. The dust jacket art also represents changes in graphic design and marketing in Canada over an extended period. By obtaining multiple copies of every title I have uncovered numerous binding variants. For example, during the Second World War there was a serious shortage of paper and binding material. In the process of binding a book, it was common to run out of cloth before completing the print run. So the bookbinder would complete the process by binding the remaining books in a material with a similar colour or texture. In most cases it is difficult to determine which colour or texture came first. Several years into collecting the ggs I decided to write a descriptive bibliography of all English-language first editions, which would include a chronicle of the publishing history of the Awards. Library and Archives Canada (lac, formerly the National Library) in Ottawa is missing many of the editions which are included in my collection. In addition, lac’s early policy was to discard the dust jackets on their copies. This meant the only way for me to document all of the English-language first editions was to collect them myself. To my knowledge, no comparable collection exists in public or private hands.

To add further depth to my collection, I have had some success in locating relatives of deceased authors. There is a lot of relevant material in their hands, just waiting to be found. Some of this may be authors’ correspondence with their publishers, family copies of rare editions (possibly inscribed to a family member), and oral reminiscences from the author’s family. This is when the skills of a detective become invaluable. Just tracking down a relative who may have a different surname can be an enormous challenge. Every book collector has at least one or two ‘holy grails’ required to complete a collection. Mine, for this project, was the very first winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction: Bertram Brooker’s Think of the Earth, published in Toronto in 1936 by Thomas Nelson & Sons, and in London by Jonathan Cape. After a couple of years of searching for this elusive title in bookstores and on the Internet, I decided to take a different approach. I gave myself twelve months to locate and purchase an important copy. Brooker’s book had been recently reprinted for the first time. It dawned on me that the publisher of the reprint would have needed a first edition to reprint from, since there was only one initial printing for the Toronto and London editions. I contacted the publisher who did the reprint, only to be told that the editor for the book was no longer with the firm, and that she tracked down a copy, which they used to produce the new edition. Sounds simple. Unfortunately, the editor had gone through a divorce, changed her name, and moved to another province. Another three months of research helped me locate the editor through a professional organization she once belonged to. She put me in touch with the grandson of the author.

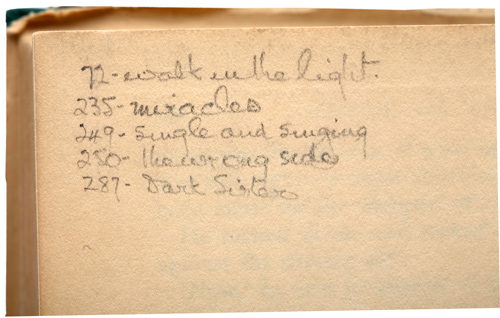

Six months later, after dozens of telephone calls with the family, I acquired the author’s reading copy of the book, with the author’s notes on the rear endpaper highlighting certain passages. This copy is significant in that Brooker read from it at the first gg Awards ceremony, held at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall on 24 November 1937. This was the best copy imaginable, other than the dedication copy.

The second phase of the project has involved writing a descriptive bibliography and tracking down publication data from 50 publishers. Over the past decade I have travelled for more than six months across Canada and the United States, conducting research at every major publisher’s and author’s archive related to the fiction list.

This has also involved thousands of emails, many letters, and hundreds of telephone calls soliciting publication data. It has been a tremendous challenge to coax existing publishers to take the time to search their files and archives for publication data. I’ve also researched copyright records at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and the Canadian Intellectual Property Office in Gatineau, Quebec. I was able to piece together the publishing history of many titles through these records. The third phase of the project was establishing a non-profit foundation to exhibit and tour the collection across Canada. I established the W.A. Deacon Literary Foundation (dlf) in April 2008.

It is named in honour of William Arthur Deacon (1890–1977), Canadian literary critic and editor. Deacon championed many of these early authors at an important time in the development of our country’s literary voice. It is in the spirit of Deacon that the dlf operates. In 2009 I was asked by colleagues from three eastern universities to provide a ‘case study’ on the Governor General’s Literary Awards for the Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing website. During my research that year my friend Dr Carl Spadoni, at McMaster University, located a private letter dated 1940 from William Arthur Deacon to Ellen Elliott of Macmillan Canada in the Macmillan archives. This letter has established that it was Deacon himself who came up with the idea of starting a national literary award. During the 1934–1935 period, Albert H. Robson, Toronto branch president of the Canadian Authors Association (caa), queried Deacon for ideas on how to impress upon the public that books produced in Canada were high quality.

By early 1937, final discussions took place between Dr Pelham Edgar, caa national president, and the Governor General of Canada, Lord Tweedsmuir (John Buchan), himself an author. Tweedsmuir gave permission to use the name of the Governor General’s office for the awards in perpetuity. Initially the caa, as agreed by the Governor General of Canada, controlled all aspects of the Awards, including jury selection. At first the judging was shared by the caa and the Royal Society, a relationship that proved unworkable. Fellows of the Royal Society were choosing books that the public had no interest in, which consequently did not benefit the authors. The three caa members, whose names were never announced publicly, controlled and built the early juries. They included William Arthur Deacon, Dr Pelham Edgar, and Leslie Gordon Barnard. In private, Deacon referred to himself and his two colleagues as the “supreme committee and supreme judges.” The caa’s objective from the start was to aid the sale of Canadian literature. Once the Canada Council for the Arts took over administration of the Awards in 1959, jury selection changed. The list of jury members chosen by the Canada Council, in both past and present, are some of the most respected authors and scholars residing in Canada. Many of the jurors were past recipients of the Award. As categories were added, the juries were expanded to meet the need. I challenge anyone who says that the ggs are insignificant since they are administered by a government body. Authors’ peers and important Canadian scholars are choosing the winners! There are some fascinating stories behind the publication of many of the winning titles. For example, Dr Philippe Panneton, a physician, academic, and diplomat, wrote Thirty Acres under the pseudonym Ringuet, his mother’s family name. Originally published in French as Trente Arpents (Paris: Flammarion, 1938), it is an important novel of early Quebec life. Hugh MacLennan is quoted as saying that he could not have written Two Solitudes (1945) without having read Thirty Acres. There are two distinct Canadian editions of this title, both published in late 1940. Macmillan (Canada) initially ordered 500 sewn sheets from Macmillan (London) for the Canadian market. After great reviews were published, Macmillan (Canada) decided to re-typeset the novel and print 1,755 copies. The Canadian edition was printed by T.H. Best Printing Co. Ltd., Toronto. Gwethalyn Graham’s Earth and High Heaven (1944) has the distinction of being one of the first Canadian novels to achieve best-seller status in the United States. An important, timely novel about race relations, it was first published serially in Collier’s (26 August–16 September 1944). The Literary Guild (club edition) and the trade edition, combined, sold 665,000 copies by late June 1945. I have identified seven trade edition printings. There were also two separate Jonathan Cape editions (printed in Toronto and London). The first printing of the J.B. Lippincott trade edition in a decent dust jacket is a scarce book.

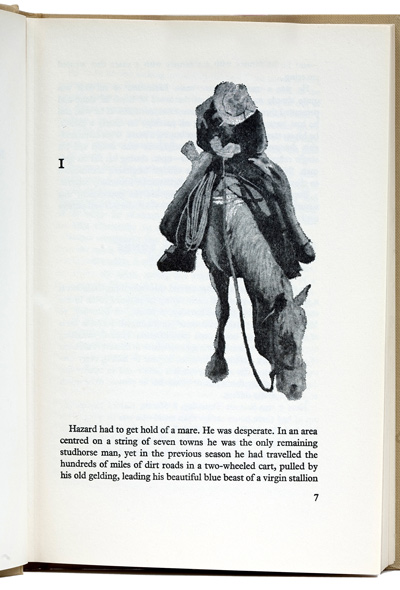

Published to rave reviews, Hugh MacLennan’s Two Solitudes (1945) was considered an instant classic. Its publication history is very complex. After the initial printing of 4,500 copies by The Vail-Ballou Press, all additional copies were printed by H. Wolff, New York. The American trade edition, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, published on 17 January 1945, preceded the Canadian edition, William Collins and Sons, that was released in April 1945. Most Canadians were introduced to this book through the American Book of the Month Club (bomc) edition that was distributed only in Canada. This copy is the rare first trade edition, first printing, bound in dark grey cloth with a $3.00 price on the dust jacket. There are three binding variants of the trade edition: dark grey, deep blue, and dark reddish orange. The bomc and trade publisher shared print runs. The dust jacket, designed by Lisbeth Lofgren, was inspired by a vintage photograph of the Chateau Frontenac Hotel above the houses of Quebec’s Lower Town. The production standards for the British edition were inferior to the American and Canadian editions. The materials used for the binding and paper are very poor. On all copies I have inspected, the publisher has misspelled the author’s surname on the binding’s spine, omitting the “a” in “Mac.” The British edition was published in 1945, but bears a 1946 date on the title page. Gabrielle Roy is considered by many to be one of the most important Francophone writers in Canadian literature. There are two French versions of Bonheur d’occasion (Second-hand Happiness), later translated as The Tin Flute. The first was published in 1945 by Société des Éditions Pascal in two volumes. In 1965, Librairie Beauchemin published an abridged French version. The original French version won the prestigious Prix Femina in 1947. The Reynal & Hitchcock edition of The Tin Flute (1947) was translated by Hannah Josephson. This, Roy’s first novel, gave a starkly realistic portrait of the lives of people in Saint-Henri, a workingclass neighbourhood of Montreal. This edition was distributed in the United States and Canada, where it sold more than 600,000 copies. It was a Literary Guild of America selection for May 1947. That same year, Roy became the first woman admitted to the Royal Society of Canada. The McClelland and Stewart edition was printed (5,000 copies) after that publisher had ordered and sold 12,500 copies of the Reynal & Hitchcock edition. David Harry Walker is the only recipient to have won the Award in two consecutive years. His first win was for The Pillar (1952), a war novel influenced by his experiences in the military. The Canadian and British edition was published by Collins (London) in a single printing of 25,000 copies. There was also an American edition (three printings) published that same year by Houghton Mifflin. The following year his comic novel Digby (1953) was published, which also won the Award. Again the book was published by Collins (London), this time in two printings of 20,000 and 8,000 copies. Houghton Mifflin published the American edition in a single printing of 6,270 copies. The next year, one of the gg jurors, Claude T. Bissell, then vice-president of the University of Toronto, quit over the decision to give the Award to Igor Gouzenko. (Gouzenko was a Russian cipher clerk at the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa, who defected with about 100 telegrams and other classified documents he’d stolen from a consular safe, exposing an extensive espionage ring operating in North America and Britain at the end of the Second World War. He has been credited with launching the Cold War.) In a letter to W.A. Deacon, editor at the Globe & Mail, Bissell said he did not consider The Fall of a Titan (1954) to be a serious contender for the Award. He felt the best novel that year was Leaven of Malice by Robertson Davies: “The Fall of a Titan was, admittedly, a potent pot-pourri of journalism and politics with some skilful literary echoes. It was not, by any standards, a good novel, and I am convinced that future historians will look upon it as a literary curiosity.” It appeared Gouzenko was being rewarded for his defection and not his literary talent. It was also published in the United States the same year by W.W. Norton & Company and became a Book of the Month Club selection. Gouzenko, who was also an artist, embellished many copies of his novel with drawings or sketches on the front free endpapers. The Canada Council for the Arts, soon after taking over administration of the Awards, began commissioning special presentation copies. The Queen’s Printer notified Douglas LePan on 17 March 1965 that he had won the Governor General’s Literary Award for his novel The Deserter (1964). The Governor General, Georges Vanier, gave a special presentation copy, an art binding (reliure d’art), to the author at a ceremony at Rideau Hall on 26 April 1965. This copy was rebound by Louis Forest in full leather with a red and gilt design on the front and rear covers, with ornate gilt tooling. Beginning in 1973, master bookbinder Pierre Ouvrard was commissioned to create an art binding for each of the winning titles for presentation to the authors. Ouvrard produced more than 300 original bindings for the Awards until his retirement in 2004. In 2005, Lise Dubois took over, producing her own unique presentation bindings. Margaret Laurence, best known for The Stone Angel (1964), the first in the fivevolume Manawaka series, is one of our country’s most beloved authors. Although she didn’t win a gg Award for this novel, she did win the first of two ggs for A Jest of God (1966). The text of the McClelland and Stewart edition of it was offset from the Macmillan (UK) edition. The book was printed simultaneously in cloth (2,000 copies) and paper (7,740 copies). There are two issues of the cloth edition. The first issue, in sewn signatures, measures 20.4 x 13.1 cm, while the second issue, perfect bound, measures 19.8 x 12.8 cm. It appears that a small portion of the soft cover issue was bound (possibly rebound) in hard covers to meet the demand for cloth-bound copies. The paper used for the first edition is very acidic, thus it has become difficult to locate collectable copies today. The dust jacket design for the M&S edition is a modified version of the Warren Chappell design for the Alfred A. Knopf edition, which was a larger format. The publication history of Alice Munro’s Who Do You Think You Are? (1978) is part of Canadian literary legend. In an interview with Carole Gerson, published in Room of One’s Own (vol. 4, no. 4, 1979: 2–7), Munro explained the publication history of the book. Her agent had submitted the collection of stories to Knopf, her American publisher, and Macmillan Canada in the spring. They both agreed to publish the collection. However, they thought the stories were about the same character and suggested she write more stories to complete the book. The American publisher was willing to wait, but Macmillan wanted to publish that fall. Munro corrected Macmillan galleys in September. Meanwhile, she was writing additional stories for the American publisher. After completing two more stories and incorporating them into the manuscript for the American book, she realized she had a much stronger book about one person. She then approached Macmillan about the changes. They said the book couldn’t be changed at such a late date. “I kept arguing that it had to be changed. Eventually they called the production manager in and said that it could be taken off the press and be completely reset, hiring overtime people, at a cost to me of about $2500 which my contract said I had to meet if there were changes this late. So I said okay. I think it was the right thing to do.” It was published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf (1979) and the United Kingdom by Allen Lane (1980) under the revised title The Beggar Maid. Sometimes publication was affected by an editor’s demands. George Bowering had initially sent the manuscript of The Dead Sailors (working title) to his regular publisher, McClelland and Stewart, as a previous contract required. His editor at m&s felt the novel needed significant rewriting. Bowering later offered the manuscript to Julie Beddoes, senior editor at General Publishing, because of the association with Robert Kroetsch, who Bowering felt had the same attitude toward “history.” The manuscript for Burning Water (1980, final title) was handwritten in three bound notebooks purchased in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Bowering had initially requested that General reproduce the ship logos from the notebooks on the novel’s endpapers. Ultimately the publisher reproduced the logo of a sailing ship at the first chapter. This is a difficult title to locate in collectable condition because of the fragile gold foil dust jacket. Several titles that have won the Award were the author’s first book. Nino Ricci wrote his first novel, Lives of the Saints (1990), for his m.a. in Creative Writing at Concordia University. Gary Geddes of Cormorant Books offered to publish it, but recommended that Ricci first try a larger commercial house. After several large publishing houses turned it down, Ricci signed a contract with Cormorant. A month or two after the contract was signed, Ricci met Peter Day of Allison & Busby (W.H. Allen) at the pen conference in Toronto. Day took the manuscript with him and read it on the plane; before setting down at Heathrow, he was determined to publish the book and proceeded to buy U.K. and Commonwealth rights. The Cormorant edition was published simultaneously in cloth (400 copies) and paper (1,514 copies). The title for the Alfred A. Knopf edition, published the following year (1991), was changed to The Book of Saints. This work is the first volume in a trilogy.

Several titles that have won the Award were the author’s first book. Nino Ricci wrote his first novel, Lives of the Saints (1990), for his m.a. in Creative Writing at Concordia University. Gary Geddes of Cormorant Books offered to publish it, but recommended that Ricci first try a larger commercial house. After several large publishing houses turned it down, Ricci signed a contract with Cormorant. A month or two after the contract was signed, Ricci met Peter Day of Allison & Busby (W.H. Allen) at the pen conference in Toronto. Day took the manuscript with him and read it on the plane; before setting down at Heathrow, he was determined to publish the book and proceeded to buy U.K. and Commonwealth rights. The Cormorant edition was published simultaneously in cloth (400 copies) and paper (1,514 copies). The title for the Alfred A. Knopf edition, published the following year (1991), was changed to The Book of Saints. This work is the first volume in a trilogy.

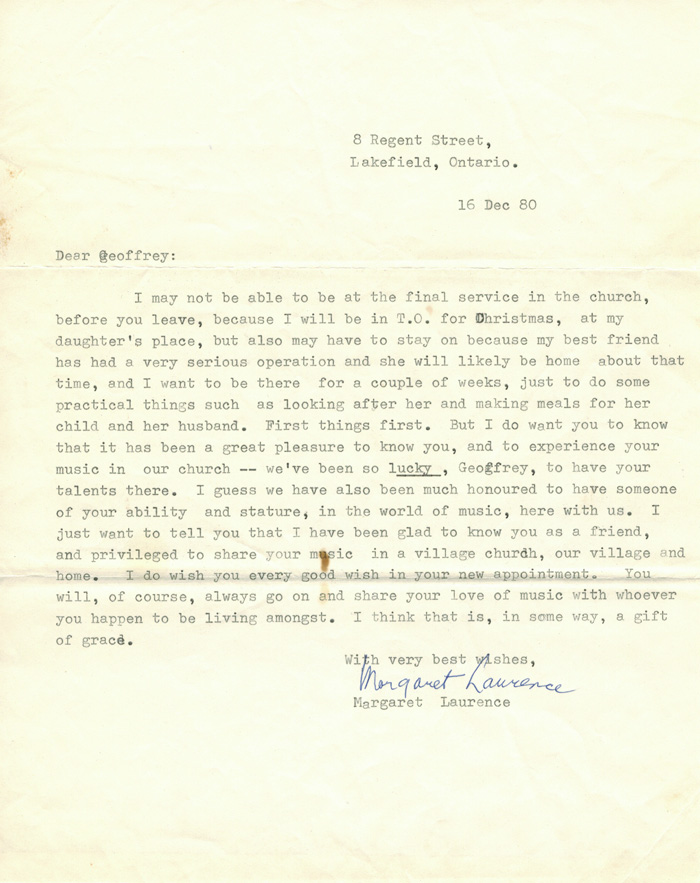

In addition to books, I have collected gg authors’ letters discussing their award-winning book. These include two Hugh MacLennan letters, addressed to a New York author, discussing Two Solitudes a month in advance of publication; a Gabrielle Roy letter discussing The Tin Flute; a Germaine Guevremont letter discussing her background and hunting birds in The Outlander; an Igor Gouzenko letter addressed to the Chairman of the Governor General’s Awards Board thanking him for choosing The Fall of a Titan; and a Margaret Laurence letter addressed to a musician at her church in Lakefield, Ontario, laid into an inscribed copy of The Diviners.

Throughout the years this project has been a labour of love. I have spent thousands of hours locating and purchasing the best copies available. The most exhilarating part was finding that elusive book I had been seeking for years. Today I am still excited to obtain an edition that I have never seen before, an association copy, or a rare advance state. It is difficult to stop, for there is always something else to add to the collection. It is difficult to explain the tactile pleasure of holding some of this rare material in my hands. Whether it is an inscribed book, a personal letter, or some other literary material that the author has handled, it is very exciting. I feel both privileged and grateful to have had the opportunity to own and examine this material. Now I would like to share some of that excitement with others, particularly the many immigrants who came to this country for a better life. Many of them, like me, have not had the opportunity to study Canadian history in school. Over the past decade I have read the majority of the winning fiction titles. That reading has given me a physical connection with Canada. The historical novels, the novels of the immigrant’s experience, and others have provided me with an education about my adopted home. Nonetheless, I have asked myself, on several occasions over the past decade, whether I was committing financial suicide by investing my life’s savings, and over a decade of my time, to build this collection. I am convinced that I made the right decision, because the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction is so important to Canada’s culture, even though other awards have also had an impact. Several other awards have actually changed our perspective on Canadian literature. Ironically, it has taken literary awards, outside Canada, to draw attention to our writers and their work. The Man Booker Prize is one of these. Several major Canadian works have won the Booker, including Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient (1992, also a gg winner); Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin (2000); and Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi (2001). Carol Shields won the Pulitzer Prize for The Stone Diaries (1993, also a gg winner). I believe Mordecai Richler’s statement to be true: “Actually, when it comes to knocking the Canadian cultural scene, nobody outdoes Canadians, myself included. We are veritable masters of self-deprecation.” We seem to have an inferiority complex about the quality of our literature. This may simply be the result of living in such close proximity to the 10,000 pound elephant which is the United States. We are constantly being bombarded by American culture in print and film, which overshadows our own literary voice. This makes the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction especially important. It is my hope and desire that exhibiting highlights from my collection will educate and excite the public about our outstanding literary history.

John H. Meier, Jr.

Delta, British Columbia